Reading Herodotus spatially in the undergraduate classroom, Part I

This is the first of three posts reporting on the deployment of the Hestia toolkit to teach Herodotus’ Histories in two college classrooms at the University of Texas at Austin (and to introduce the historian’s work to one high-school Latin class). This post focuses on the reaction of high-school and lower-division college students to the Hestia narrative timeline as a supplement to traditional instruction based on printed texts.

On June 6th, the Hestia2 project will hold the last of its four seminars: this one will focus on the use of digital tools in teaching and public engagement, and the connection of digital pedagogies with scholarly research. It therefore seems like an especially good time to discuss the results of a year-long experiment with the Hestia toolkit — primarily the narrative timemap, but also the ARK database — in one lower-division and one upper-division Classics course at The University of Texas at Austin.

In the last five years, it has become conventional wisdom that undergraduate students now arrive at their universities as “digital natives”, so steeped in online culture and interactive apps — and with such short attention spans — that they cannot be reached by analog teaching methods. MOOC boosters and flipped-classroom enthusiasts alike have insisted that the “sage on the stage” lecture model is dead, and that higher education can only survive by replacing this with “guide on the side” pedagogical strategies. In the US, at least, this is a contentious claim (Jonathan Rees’ blog More or Less Bunk offers one of the more protracted and coherent critiques). Nevertheless, even detractors of the current direction of digital education generally acknowledge that digital tools can be valuable additions to the classroom. Yet the discussion about what digital platforms work for what pedagogical purposes is still underdeveloped.

At least in the humanities, most MOOC proponents and digital pedagogues seem to assume that “interactive” is good in theory, while in practice relying mainly on short videos and digital variations on the multiple-choice-quiz theme. Meanwhile, a smaller number of projects focused on more complex and experimental interactive tools work more on the “if you build it, they will come” principle. My own experience suggests that neither of these models is ideally suited to undergraduate learning, and that while students may be “digital natives”, they are natives only in very narrow ways. The video/multiple choice quiz combination reinforces this narrowness to the detriment of active learning, but complex interactive platforms fall outside it altogether. To take advantage of the instructional possibilities of innovative interactive tools, we will have to find ways to engage student users not as natives, but as exchange students.

The digital context in which undergraduate students are truly natives is that of consumption. My students generally self-report as expert consumers of digital media: they stream movies and TV shows online, and most spend time on YouTube; they post on Facebook and Instagram; they Google answers to their questions. They are not always as information-literate as their instructors hope — exercises that ask them to find information about the ancient world routinely return a number of commercial or fringe websites — but for the most part, they have received basic training in high school to distinguish between reliable and unreliable online sources. Ironically, many of them have been told never to use Wikipedia for research, even though its editorial standards are higher than those of most websites, because “you don’t know who wrote the information”.

Despite those warnings, though, most of them do use Wikipedia, because what they are usually looking for — at least in large lower-division lecture classes that meet distribution requirements and are attended by first- and second-year non-major students — is reference information. The most attractive sources, like Wikipedia, are the digital equivalent of those rows of World Book Encyclopedias that graced countless middle-class bookshelves in the mid-20th century. These sources offer condensed, easy-to-understand, simplified and fact-heavy overviews of the subjects and characters that students encounter in humanities lectures — and students are very good at finding and using them. The other sort of digital resource they’re interested in is that which might improve their grades: study guides, flashcards, practice or sample exams, summaries of primary sources, etc. Almost all my students have used a course-management system of some sort (usually Blackboard or Canvas) where these sorts of study aids are a familiar feature.

In my experience, then, most students are digital natives in the classroom only when it comes to videos, reference material, and study aids — and then primarily only when it comes to manifestations of those resources in familiar forms. They are much less familiar and much less comfortable with tools that digital humanists take for granted: spreadsheets, databases, visualization platforms. They are also much less likely than the creators of interactive websites to be open to serendipity and undirected exploration. I learned this the hard way with GeoDia, an illustrated, interactive spatial timeline of the ancient Mediterranean. My collaborators and I built the site to encourage free-form comparison and discovery between sites of different cultures and periods. Narratives were deliberately absent, so that students could build their own contexts for material culture in time and space without being forced into the traditional stories told by textbooks.

The students in the first few classes that used this platform didn’t do that. Not only did they not explore, almost none of them used the site to help them learn the dates, production-centers, and styles of the objects and monuments they were required to discuss on quizzes and exams. This was not because they couldn’t figure out how to use the site (though more people had difficulty with the map/timeline mashup than we’d anticipated), nor because they didn’t like the concept (most thought it was an interesting way to look at the ancient world). It was — at least to judge from the surveys — because the material was organized in an unfamiliar way, because the site lacked the kind of synthetic framework provided by encyclopedias, and because it didn’t map clearly onto the course content the students expected to be tested over. End-of-semester survey responses repeatedly included requests to add more encyclopedic information and make the image resources coincide more completely with the textbook.

My response to this disconnect — one I’m still trying to work out fully — was to turn students into producers rather than consumers. Instead of waiting for them to explore GeoDia on their own until the ancient world started to make more sense, I began to assign them group projects that required them to start telling or illustrating their own stories about the ancient world. GeoDia moved into the background, as a formatting model and a place where the best student-produced content could be made public, but not as a pedagogical tool in itself. I retained the focus on time and space that I had intended GeoDia to convey — but now, I had the students doing the geotemporal mapping themselves. This built on one of the digital areas in which many of them do feel fairly “native”: digital maps, which most of them have already encountered in one form or another (Google Earth, Google Maps, mobile-phone mapping applications, even location tags for photos in Facebook or Flickr).

This is where the Hestia narrative timemap of Herodotus’ Histories comes in. I agreed to carry out an educational pilot for the Hestia2 project in Fall 2013 in a large (225-student) lower-division lecture class, Introduction to Ancient Greece, because I thought it would provide an exciting departure from our traditional printed texts and a concrete demonstration of the way digital texts allow us to read spatially. My experience with GeoDia made me wary of presenting the Hestia narrative timemap to the students as a resource without connecting it specifically to course content, but I didn’t want to make it such a central feature that students began to fret about its effect on their grades. I therefore framed the interface as an optional but helpful tool that would be useful (but not required) for studying for a couple of low-stakes quizzes. I also changed one of the required texts. Usually, I ask students to buy the Landmark Herodotus, which is richly furnished with maps, but this time I had them buy Robin Waterfield’s translation for Oxford Classics instead. This edition is less expensive, but more importantly, it has fewer and less detailed maps, which I thought might encourage students to supplement their readings with the Hestia narrative timemap.

Students encounter Herodotus at the beginning of the second of three segments of this course, and read selections from books 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7 and 8 (you can find my syllabus here). The first segment deals with Greek prehistory down through the period of colonization, while the second segment covers Archaic Greece, the Persian Wars, and the rise of Athens before the Peloponnesian War. Since the course pays equal attention to literature, history, and art and archaeology, the readings from Herodotus take place in conjunction with discussions of the Archaic intellectual revolution and the development of art and architecture in the Archaic period. I place a strong focus on the influence of Egypt and the Near East on all of these areas of Greek culture, and thus it made sense to focus their use of the Hestia resources on the connections between the Greek, Egyptian, and Near Eastern worlds.

I use the iClicker classroom response system in this class, both to promote in-class engagement and to make sure that students are keeping up with the readings. I usually ask straightforward, factual questions related to the primary sources assigned for a given class. The first of the low-stakes quizzes related to the narrative timemap took the form of an iClicker question — but unlike the usual verbal questions, this one provided a map and asked the students to choose the letter that represented the site where a particular event (the death of Cleobis and Biton recounted by Solon of Athens to Croesus of Lydia in book 1) took place.

Screenshot of a slide used for an iClicker quiz in conjunction with the Hestia narrative timemap of Herodotus’ Histories. The multiple-choice letters correspond to different locations.

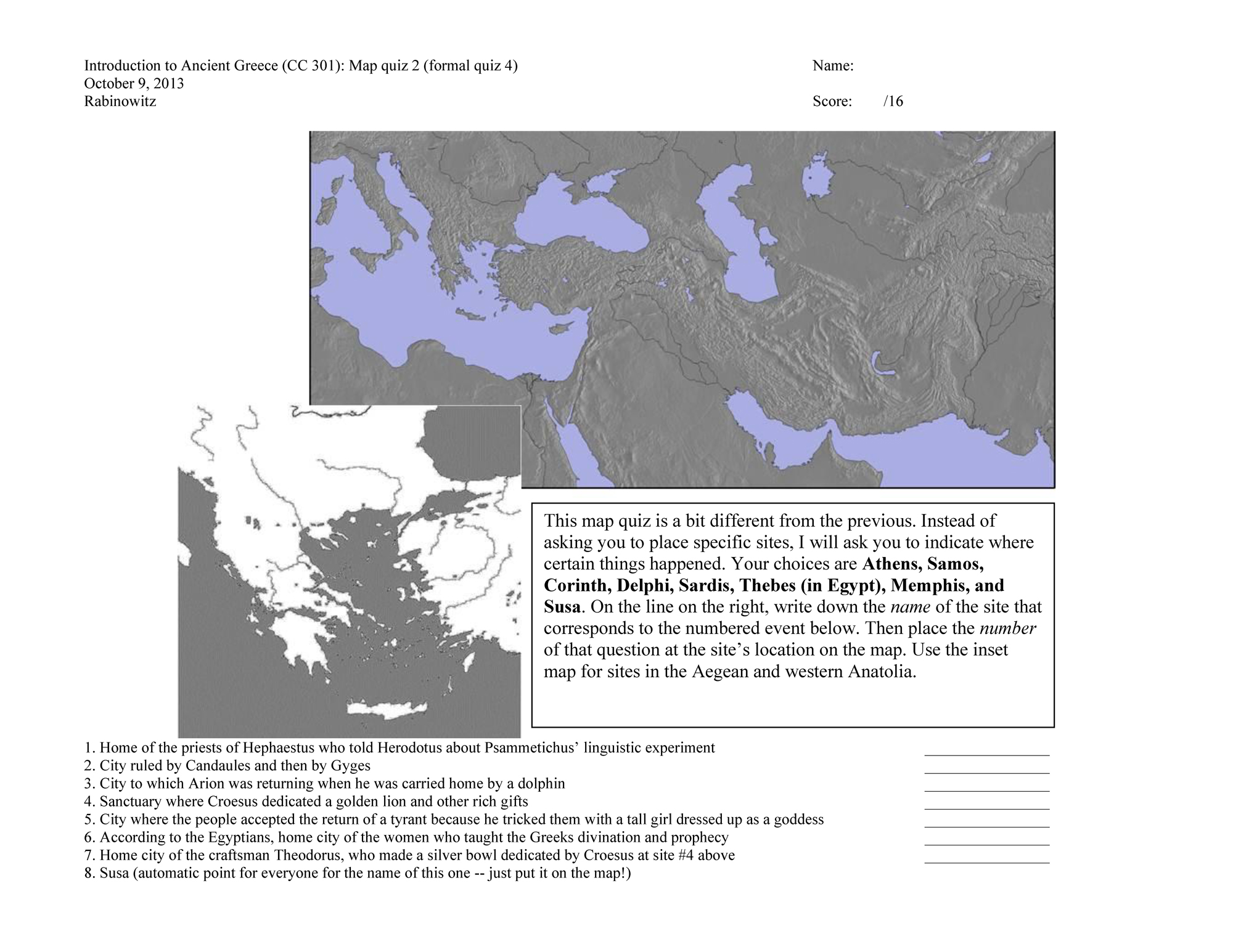

The second quiz was one of 11 more formal, graded quizzes spread over the course of the semester. These are divided among passage commentaries, slide identifications, and map quizzes — the last, which require students to locate 8-10 sites provided in advance on a blank map, are the easiest and have the highest grades. I replaced one of these map quizzes with a slightly more complicated variant: I provided the sites in advance, but asked the students not only to place those sites on the map, but to match them with events that happened at them in book 1 of the Histories. Again, this was meant to encourage the students to use the Hestia narrative timeline to consider the connection between place and event. I suggested that they use the timelne to find references to the designated places, and then see what events were described at those points in the text. The result was somewhat less successful than I’d hoped: the average for this map quiz was 80%, compared with an average of 94% on the other three standard map quizzes.

A map quiz for the course “Introduction to Ancient Greece” taught at UT Austin in Fall 2013: it asks students to associate places with events in Herodotus’ Histories.

Part of this was certainly the unfamiliar format, which required an extra cognitive step to associate place with event. But the end-of-semester surveys about digital tools in the course showed an interesting pattern that suggests another reason for this poor performance: students did not take advantage of the narrative timemap. Although most (72%) of the 113 students who responded to this section of the survey agreed or strongly agreed with the assertion that the narrative timemap was intuitive and easy to use, and an almost equal number (71%) claimed to have used it for the Herodotus readings, only 58% agreed or strongly agreed that it was useful for the map quiz.

Moreover, despite the high number of students who said they’d used the site for the Herodotus readings, 55% of the respondents indicated that they had only visited the site from one to four times during the semester (to compare, there were six class meetings with assigned readings from the Histories). 19% of respondents visited the site from 5 to 10 times, and 16% visited more than 10 times. Only a minority of students went on to explore further: 26% said they had used to the narrative timemap to read sections of Herodotus’ work that were not included among the assigned readings.

On one level, these results are encouraging: more than one student in four read more than was required! It’s hard to say, however, whether this was inspired by the interactive text, or whether these students would have read on in the Landmark Herodotus as well. It is fairly clear from these results, however, that for many respondents, the interactive Hestia resources were not inherently valuable, even when presented as aids for graded (but low-stakes) assignments. Most students in a general-education, lower-division class like this seem unlikely to explore on their own initiative beyond the material they are responsible for on higher-stakes exams and assignments. This confirms the pattern I noted with the GeoDia platform, as do most of the student suggestions for improvement of the Hestia interface. Many of the latter focused on access to more traditional forms of information: encyclopedia entries, videos or image resources that provide visual information about sites mentioned in the Histories, historical facts and dates related to people and events described in the work. In terms of user interface, many respondents, probably used to Google searching, thought Hestia should include free-text search functionality.

I think the take-away from this pilot is that students are open to more complex interactive tools for reading ancient texts, and a small number will be drawn to explore on their own — but there is a very strong desire for information to be presented in familiar forms determined in large part by Wikipedia and Google (and before them, by printed encyclopedias and indexes). A much more limited exercise with a newer version of the interactive text in a high-school Latin classroom reinforces this observation. Since the newer version corrects a number of user-experience issues that came up in the surveys from the Introduction to Ancient Greece course, the high-school test serves as a sort of control.

I will discuss the newer version of the narrative timemap, which uses the GapVis display architecture, in the following blog post. It is enough to note here that it offers significantly more information and potential for discovery for individual sites, which are now connected both to the Ancient World Linked Data ecosystem through Pleiades and Pelagios and to other sites that appear close to them in the text (a co-reference network). In the spring, I visited a Latin classroom at an Austin-area high school to talk about digital approaches to Classics, and with the permission of the instructor, I took the opportunity to get feedback from the students on the new Hestia resources (a more detailed high-school experiment carried out in August 2013 is detailed in this previous series of posts). These Latin students had been reading Caesar’s De bello gallico, so before our session, I asked them to read the Scythian ethnography in book 4 of the Histories, since it offers an interesting parallel to Caesar’s description of his “barbaric” opponents. I also asked them to explore the detail pages for some of the individual sites that they encountered in this section. We then carried out some in-class exercises focused on the discovery of reliable information about ancient places mentioned in texts (in this case, the forest of the Carnutes where the druids are supposed to gather every year).

After the class, seven of the students completed a brief online survey, and an eighth passed on some comments he had prepared in advance. Although the sample size was much smaller than that in my lecture class, very similar patterns were visible. The clearest desire was for more access to encyclopedic resources and associated visual media: again, a number of students basically wanted to be able to get from a person, place, or event in the Herodotus text to a reliable, richly illustrated Wikipedia-style summary. These students also expressed a new concern related to the increased potential for discovery in the new interface: several suggested better wayfinding tools, so that a user could go off to explore related sites but still be able to get back to his or her starting point. This echoes a caution expressed by one of the respondents to the Introduction to Ancient Greece survey: too much information can be overwhelming, especially when it’s not highly structured.

I suspect that these experiences with high-school and lower-division college students are representative of the reactions of students at this level across the boards. Today’s first-year undergraduates are not “digital natives” in the sense that they embrace interactive, serendipitous, unstructured, hyperlinked networks of digital data. They are “digital natives” in the sense that they are comfortable using digital tools (Google search) to find and consume information packaged as the digital equivalents of traditional encyclopedias (Wikipedia) and instructional videos (YouTube or Khan Academy).

This means we can’t assume that they’ll come if we build the sorts of interactive, innovative, discovery-oriented interfaces we find interesting as digital humanists. If we want them to come and stay, we can’t just wait — we have to meet them where they are and lead them down the path. I think there are two ways to do this, one on the side of the resource developer, the other on the side of the classroom instructor. On the side of the developer, efforts can be made to connect an interactive interface to more traditional and familiar forms of information — by adding structure, multimedia resources, links to encyclopedia entries. This is one of the directions the Hestia2 project is taking, in collaboration with the Open Learn initiative at the Open University.

On the side of the classroom instructor, by contrast, interfaces like the Hestia narrative timeline can facilitate the transformation of students from passive consumers of digital information to active makers of digital knowledge. In the Introduction to Ancient Greece class, I had students work in groups on semester-long projects to create event- or image-based narratives for display in the TimeMapper interface created by the Open Knowledge Foundation (information about these assignments is available here). The Hestia narrative timemap helped to familiarize the students with the idea of a narrative integrated with a map, and it seems also to have given some of them a better idea of how Herodotus constructed his own story: 51% of the survey respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that the Hestia interface helped them to see patterns in the work that they would not have noticed in the text alone.

The transformation from consumer to maker is not an easy one, and it requires close attention to course design and a high tolerance for trial-and-error on the part of both instructor and students. It is starting to take hold as a model, however, and there have already been notable successes like the Perseids project associated with the Perseus website. In the following blog post, I’ll write about my attempts to design an upper-level undergraduate historiography seminar for Classics majors in which Hestia resources would serve as a catalyst for such a transformation — and in my third post, I’ll report on the results, from both my perspective and that of the students.

Header: Archaic kouroi identified as Cleobis and Biton in the Delphi Archaeological Museum. From photo by Adam Carr on Wikimedia Commons, CC-zero.

You must be logged in to post a comment.