Beyond images and surfaces: Impressions from the ‘Telling stories with maps’ symposium in Birmingham

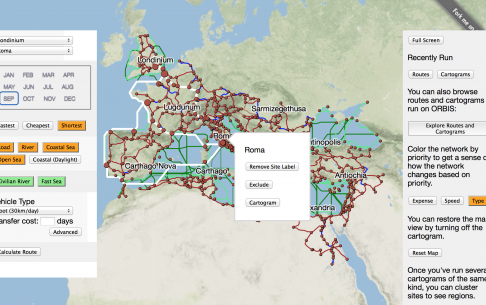

As we have already written on this blog, the fourth event within the Hestia 2 programme recently took place in Birmingham. With its focus on qualitative GIS and narrative mapping, this symposium was closest to my own academic interests and motivations for participating in the project. Its selection of papers, audience and topics achieved one of the long-standing aims of the Hestia team: to bring together the social sciences, humanities and the ‘IT crowd’ in a genuine interdisciplinary dialogue. Testifying to the success of the event were the high attendance rate, the diverse professional backgrounds of participants, and the numerous follow up discussions instigated on different fora (particularly twitter and the ‘blogosphere’).

Read More»