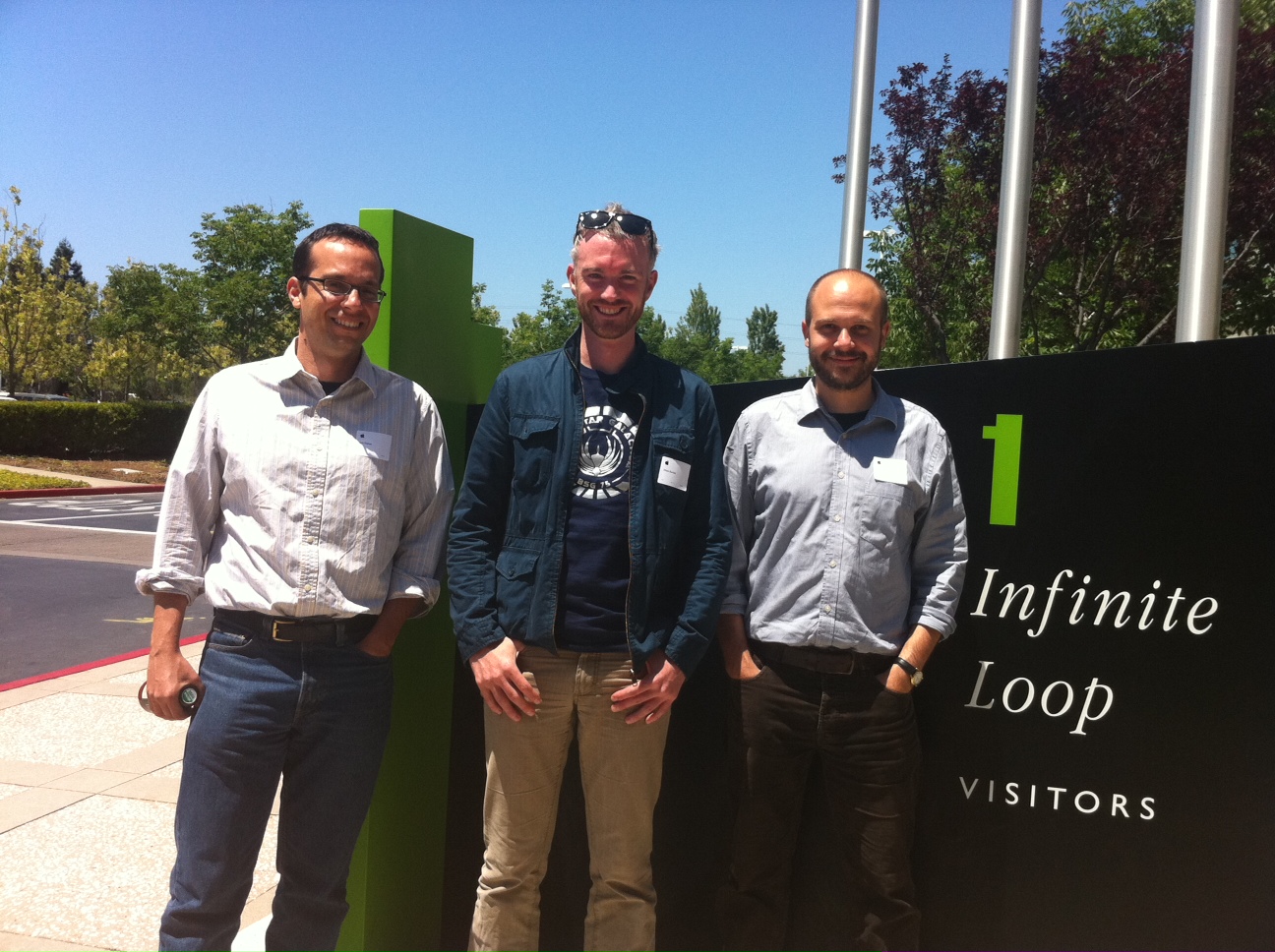

Back in November Hestia2 held its second seminar in a place where the sun really does always shine (see below): Stanford, California. There was a very good reason, in addition to being able to wear a t-shirt in November, for holding a seminar on Digital Humanities in Stanford. With its campus in Palo Alto, Stanford shares a location with a number of high-tech household names, including Apple, Google and Facebook, while smaller start-ups in the San Francisco Bay Area are but a short Caltrain ride away. One of these, Farallon Geographics, has recently worked with the Getty Conservation Institute and World Monuments Fund, to produce an open-source, web-based, geospatial information system for cultural heritage inventory and management, called Arches, showing the massive potential for collaboration between private digital enterprise and the public cultural sector, including higher education.

Read More»News

The Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis is proud to host the next Hestia2 event, on November 4-5 in Wallenberg Hall at Stanford University. During this free one and a half day seminar we will explore network analysis and uncertainty in data from a number of different perspectives. It will also be an opportunity to take a sneak preview of a number of new and exciting projects.

Read More»

Last month we organised a seminar on linked data and spatial networks in Southampton. Videos and slides of presentations of the seminar are now available on The Connected Past website. There are hours of footage and books-worth of slides on there for you to enjoy! This was only the first in a series of Hestia2 events. More info on Hestia2, future seminars and online resources can be found on our new website. Looking forward to seeing you at one of our future seminars!

Read More»In spite of the frustrations documented in the last post, our trial was a truly useful experiment in making academic research more open to and usable for a broader audience, and we can be hopeful about indications for future productive collaborations. We believe that the positive outcomes outweighed the few negatives, and that the obstacles were not intractable.

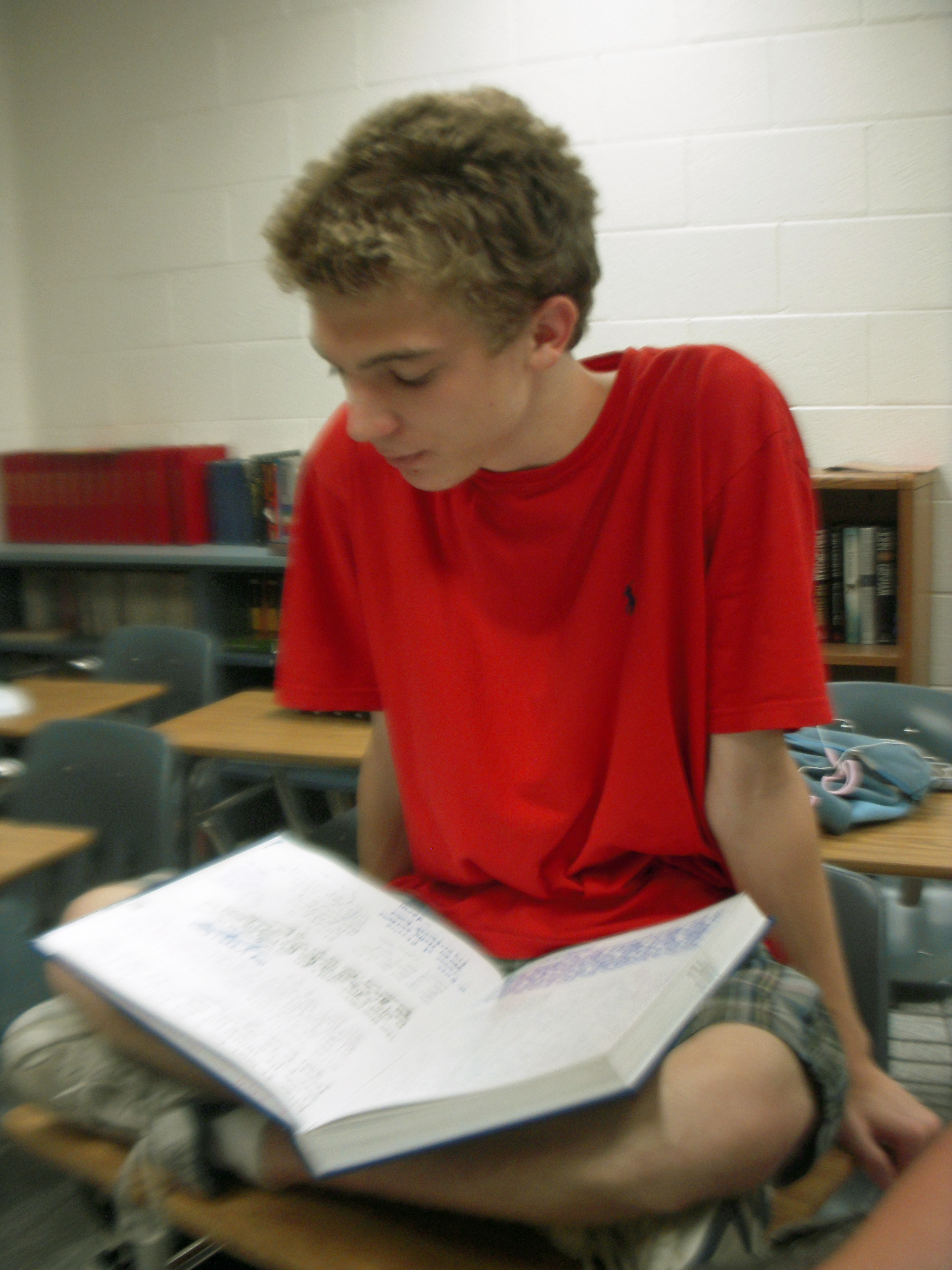

Students felt that they could engage with the primary source material, which is a rare opportunity for ninth-graders. As a consequence, students felt a stronger sense of ownership of their own study, thereby supporting Dewey’s goals for the democratization of education. In time, we should be able to see whether students also reinvest their interest in Classics as a subject that provides them with unique opportunities to participate as researchers.

Read More»It was not all plain sailing, however. Inevitably, we encountered problems and frustrations with conducting this trial. What Elton and I learned, and what we document here, may help to inform how to design and conduct future collaborations, because the obstacles largely address infrastructural concerns, or pragmatically, “getting work done on the ground.” The researchers themselves felt that they were not fully able to carry out the trial as thoroughly as they might have because of the school syllabus and timetable.

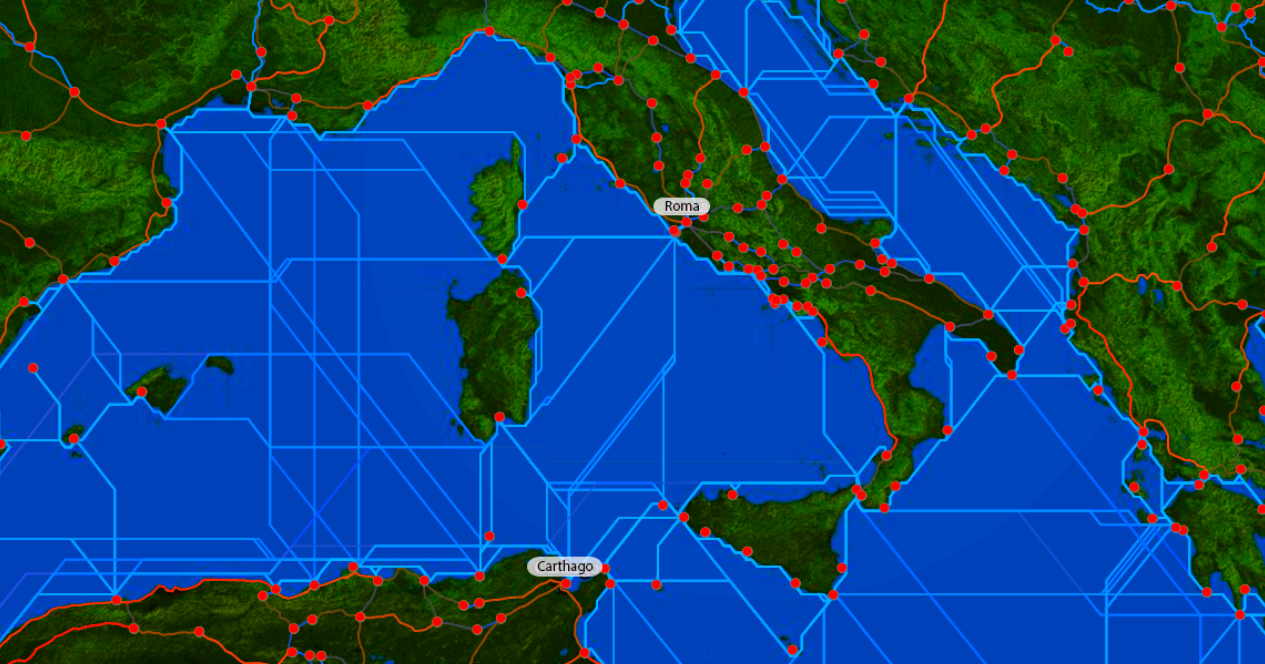

Read More»Encouragingly, the results showed that the students enjoyed using Hestia, particularly the ability to scan the ancient locations and find out about what Herodotus says about them using GoogleEarth. Initially we thought that was accounted for by the fact that GoogleEarth was new to students and that they enjoyed the novelty of seeing the world from satellite. Rather than GoogleEarth’s novelty, most of the students were already seasoned users of the application. So it appears that Hestia was building upon their technological familiarity.

Read More»One of the ways that my collaboration with Hestia added to my own “pedagogical toolbox” as a teacher was working with Elton to design the survey. The survey itself had to target a student audience and, at the same time, deliver robust information for the research team. I had a lot of experience and interest in writing good questions and assessments to evaluate student mastery, but I did not have a lot of experience thinking in survey metrics.

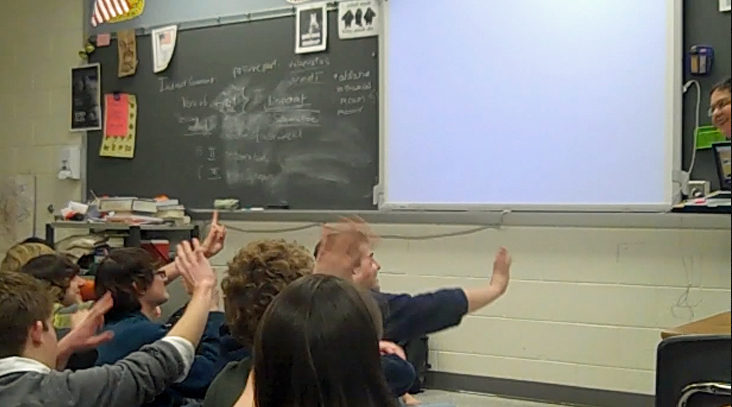

Read More»As I concluded the first installment of this story, we left off with Elton and myself considering a robust pedagogical framework that would guide our decisions about involving the students during their classroom time. We were hoping that the lessons would be interesting but also would convince educators that our goals aligned with other school goals for curriculum and school improvement. Therefore, some of the consequential, overarching philosophical questions we pondered were: Can a digital lab work? How can it work? What consequences might it have? What potential might there be to share or to extend the practice?

Read More»In 2010, the Hestia team worked together with a high school in the US state of Virginia to experiment with different ways of thinking about Herodotus’s Histories using digital resources. In the next series of posts, Chris Ann Matteo, formerly an Outreach officer for the American Philological Association (APA) and a teacher of Latin in Loudoun County Public Schools at the time, talks about the inspiration behind the collaboration.

It all started when I met Elton Barker at the final dinner of the Classical Association Annual Conference in March of 2009 in Glasgow.

Read More»As the organiser of the Hestia2 seminar in Southampton I could write about our initial struggle to find a good format, my fight with the university to book a seminar room in a completely booked out campus, discussions with our financial support staff to figure out a balanced budget, the technical flaws with our livestream feed, and of course the many very human feelings like “no-one will turn up!?!” and “what shirt should I wear?”. But none of that would be very interesting to read, and all of these concerns are now firmly pushed to the back of my mind and replaced by the feeling that this seminar was a success!

Read More»